Neuroscience of the Covid-19 Crisis

Human adaptability and resilience have been tested more severely in 2020 than for many decades. The shock of the Covid-19 pandemic has affected us all, whether we realise it or not. Work has continued, and those who have been lucky enough to avoid falling ill have been able to carry on, if not quite normally then in an apparently sustainable manner. But, after nine months of it all, people are understandably getting tired.

Eden McCallum’s research into the business response to the pandemic has shown that while some people have enjoyed more flexibility and work/life balance in the great working from home experiment, many have also now had enough of the disruption. Liann Eden, co-founder of Eden McCallum, comments “from our regular surveys of business leaders, we see a stark deterioration in perceptions about remote working between May and November. People are particularly negative about the impact on well-being/mental health, morale, motivation, and collaboration. Also striking are the findings that men are much more negative about remote working than women.”

So what impact has the Covid-19 phenomenon had on us all, and in particular on our brains and emotional state? The firm recently hosted a conversation with Cristina Escallon to explore this. Escallon is an expert in leadership development and transformation. She lectures on neuroscience and leadership at London Business School, is a senior adviser to Ashoka, and a senior affiliate with Aberkyn and Eden McCallum.

The session started with an ‘emotional check-in’, an idea which has its origins in the aviation industry. (It was found to be an effective safety measure to ask pilots to discuss their mood candidly before they undertook another flight.) The overall picture, which Escallon has seen repeatedly this year, was very mixed; while many people were feeling gratitude and connection, there were also many feeling stress, tiredness, worry, frustration – and everything else in between.

Participants also said they were experiencing a range of physical and mental issues after all these months of the pandemic: exhaustion, a ‘foggy brain’, irregular sleep patterns, and burnout, amongst others.

Many people are in fact moving through a classic curve of a reaction to a trauma or disaster of some kind, Escallon said. There can be a kind of honeymoon recovery in mood initially, followed by a realisation that things will never be the same; and with it, disillusionment, further affected by negative trigger events. The announcement of the creation of a successful vaccine could be one of those recovery moments which could in turn be followed by further disappointment if the roll-out is not the ‘magic bullet’ many are hoping for, and the situation drags out further than we would all want.

Humans have evolved to be highly sensitive to threats – indeed, we are all the descendants of people who, in the main, successfully avoided threats. Fear of harm is a stronger response than the movement towards something attractive or rewarding.

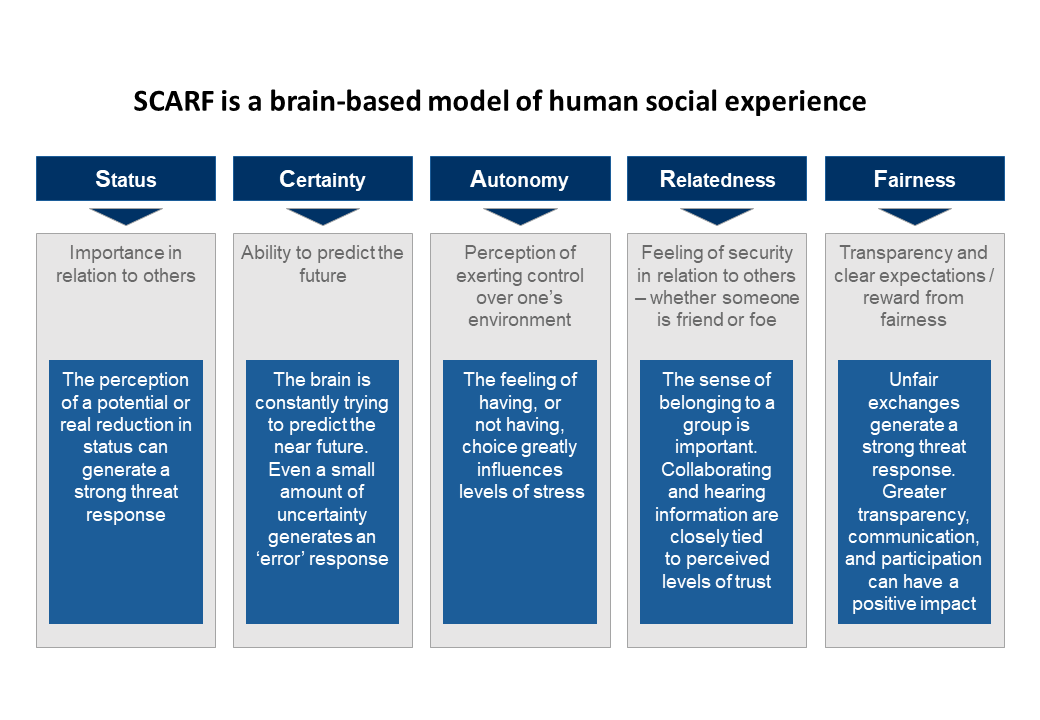

Escallon referred to the SCARF model developed by the Neuro Leadership Institute which describes what people are seeking: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.

Our brains are under threat within every single one of these headings in 2020, considering the pandemic as well as other events, Escallon noted. No wonder many people are finding it hard to cope.

The brain is a remarkable organ which responds rapidly to stimuli. As Escallon explained, at the centre is the thalamus, which operates like a kind of switchboard. Messages are sent to the amygdala, which is the primitive emotional centre. In stressful situations we can experience an “amygdala hijack”, when we may over-react to threats and bypass the rational, executive function of the brain’s pre-fontal cortex (PFC).

During an amygdala hijack, energy is diverted from the PFC, and we cannot think straight. Stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline) are released and remain in the system for several hours. We may react with a fight, flight or freeze response.

And this is where the ‘foggy brain’ sensation has its origins also. The hippocampus – the brain’s ‘librarian’ as Escallon put it – tries to find meaning and reference points in what we are going through.

But we are confused: wearing a mask might seem like a good idea rationally, yet most of us are not used to seeing so many masked faces in front of us. The brain goes into a fog, which can ultimately prove exhausting. The brain just doesn’t know what to make of all this.

So how might we try to build greater emotional resilience and flexibility? George Bonnano at Columbia University has described resilience as meaning “the ability to function relatively well in adversity”. Escallon calls it “staying grounded inside, flexibly integrating what is happening outside”.

Escallon highlighted the importance of acknowledging, particularly at this time of the year, all that we have achieved. She quoted the thoughts of Lucy Hone from the University of Canterbury in New Zealand: “This has been the year where the globe demonstrated its capacity for resilience. Look what we have managed to do.”

If we can pause, label our emotions and fears and reframe them, we can prevent the amygdala hijack and allow the PFC to function. So it is not weak to acknowledge our emotions and our fears; it is smart: it helps to deactivate the overly emotional part of the brain and bring the PFC back ‘online’. It also allows us to recognise that we are not alone in doing so, we are connecting at a human level and achieving relatedness (the letter R in the SCARF model).

And if we can manage our (mental) energy better in this way, it will become a good, healthy, repeatable practice.

Escallon said that part of managing our mental energy is creating space; we should block out time in our diaries where we have at least one hour a week to do nothing – to stop and stare, walk in nature…this is when new ideas often spring up.

In addition to creating space for ‘nothingness’, Escallon discussed other key levers for conserving our energy: staying connected with each other; finding our own life purpose, in order to find meaning in what we do and how we do it; developing a healthy daily routine; managing our sleep, amongst many more. Fundamentally, leaders need to conserve their energy for the long haul.

Leaders also need not just a Plan A, but also a B and C – to ‘hope for the best and prepare for the worst.’ The post trauma curve will manifest itself and we need to be ready for setbacks. We need to be prepared, as individuals and organisations, to manage whatever comes.

As we emerge from the pandemic it will be essential to maintain that emotional health and connection, to have that “check in” before meetings when people can discuss openly how they are feeling.

She does not believe we will go back to the status quo ante. Healthier working environments will be more human; and places where all feel seen, heard and valued.