Implications of a Net Zero Carbon Economy

Our planet is warming, and the need to prevent further damaging climate change is urgent. The good news is that while this task is daunting, it is also doable. This was the conclusion of a fascinating breakfast seminar hosted by Eden McCallum at London’s National Portrait Gallery on 5 February. The event was focusing on the implications of a net zero carbon economy.

A panel of expert speakers was led by Lord Adair Turner, Chairman of the Energy Transitions Commission and former Director General of the CBI. Also on the panel were Keith Anderson, Chief Executive of Scottish Power, Rebecca Heaton, Head of Climate Change at the Drax Group, and Tony Harper, Industrial Challenge Director at the UKRI’s Faraday Battery Challenge initiative.

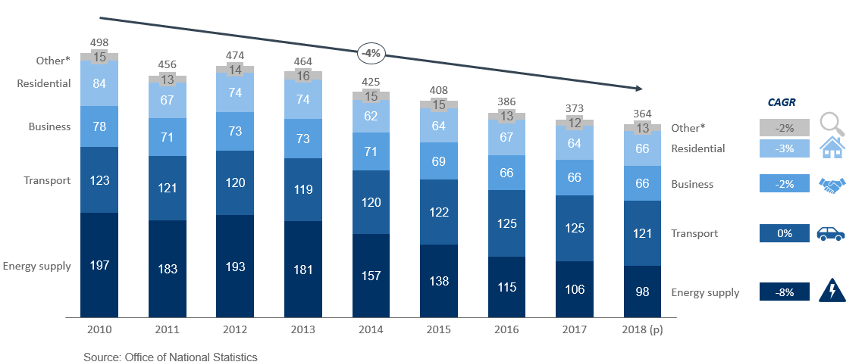

The seminar was introduced and moderated by Matthew Harwood, Global Vice President for Strategy and Sustainability for the engineering firm McDermott. He pointed out that the UK has reduced its CO2 emissions by c. 40% over the past 8 years, mostly in the energy production sector. Many levers could be used to achieve a net zero carbon economy, including reducing the demand for energy and significantly increasing electrification.

Lord Turner began his talk by reminding the audience that the earth’s temperature has already risen by one degree celsius, and the challenge is to avoid that rise reaching two degrees; 1.5 degrees would be a better goal.

But Turner said that it would be possible for the planet to achieve net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 in the developed world and by 2060 in the developing world, in line with the Paris COP agreement – and the costs of doing this are lower than people think, he added.

Over the past decade the cost of generating electricity through wind and solar has fallen dramatically, in a way that most people failed to anticipate. The costs involved in solar PV (photovoltaics) have fallen by about 80%-85%, and onshore wind by 65%-70%. Offshore wind is also a much cheaper option than it once was (having fallen from £150 to £39 per megawatt hour). In parts of the world particularly suited to generating solar – such as Chile, Morocco, Saudi Arabia – prices bid at auctions have fallen below $20 per megawatt hour.

Altogether, Lord Turner said, it should be possible for the UK to generate 85% of its electricity through renewables (solar and wind), leaving the challenge of balancing the power system, finding that extra 15% of generation for when the sun does not shine and the wind does not blow. The answer lies partly in the use of improved battery technology for storage purposes, dealing with the “diurnal cycle” (day to night generation and usage), and partly with the use of biomass generated electricity deployed with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology to address seasonal challenges.

Industry by industry, net zero is achievable, Lord Turner said – his Energy Transmissions Commission described this task as “Mission Possible” in a recent report – and not by buying carbon off-sets. The cost of achieving this in the UK is estimated at between 1% and 2% of GDP: not nothing, but not a terrifying figure either.

Residential heating is the toughest nut to crack, and helping lower income households to replace gas central heating with zero carbon electric systems will probably require government subsidy.

In response, Scottish Power’s Keith Anderson agreed that net zero was achievable and that the know-how exists to make this a reality. What government needs to provide now is an action plan and a robust policy framework, he said. It is an emergency. Simply put, the route to net zero is to “electrify the hell out of everything!”

Anderson added that government cannot do this to people – it has to be done with people. Change has to be made easier for everybody. Without the collective choices of the consumer pool, the necessary change will not happen.

Rebecca Heaton from the Drax Group echoed Keith Anderson: policy is needed and government has to act. Targets alone are not enough. Drax is the largest generator of renewable energy in the UK, she pointed out, with its biomass capacity, supported by carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. Capturing carbon “locks it away” she explained, leading to “negative emissions”.

Tony Harper from the Faraday Battery Challenge said that land transportation had to become 100% electric – although he conceded that for heavier vehicles (lorries) batteries may not be up to the job and hydrogen-fuelled engines may be needed.

But electric vehicles are becoming a more compelling proposition all the time. Range is no longer the problem, finding enough charging points is. We also need to recognise the knock-on effects of the end of internal combustion engines (ICE): currently 2.6m internal combustion engines are made in the UK every year.

The good news is that electric vehicles are already cheaper to run than ICE vehicles, and the cost of purchase is also expected to fall below prices for ICE vehicles by the mid 2020s. Zero carbon steel may cost 20% more to produce but the finished product may ultimately cost only about 1% more. Shipping can become zero carbon with the use of ammonia-based fuel. Aviation will cost more – perhaps 10%-20% on the price of a ticket – but will achieve net zero with the use of biofuels for long haul and electrical power for short haul.

Lord Turner’s judicious optimism set the seal on the discussion. We had underestimated how fast costs would fall in the past, and he believes that future innovation will make getting to zero carbon costless. The North Sea alone could be home to off-shore generation of 450 gigawatts of capacity; and 100 gigawatts of that could cover more than half the UK’s future electricity needs even in a deep electrification scenario.

A zero carbon economy is within reach if the right policy framework is set and the genius of innovation is allowed to do its work. The audience left the National Portrait Gallery with perhaps a little more hope than when they arrived.