Breaking bad habits: finding new ways to outperform the competition

A talk by Freek Vermeulen, professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at London Business School

We learn – at least, we should learn – from failure. But success is not always such a great teacher. Success is satisfying at first. But it can also lead to complacency. We may tell ourselves that our business displays “best practice”. Yet we could be slipping into bad habits, becoming vulnerable to new competitors.

This idea lies at the heart of Freek Vermeulen’s book Breaking Bad Habits – defy industry norms and reinvigorate your business (Harvard Business Review Press), and was the starting point for two presentations Prof Vermeulen gave recently to Eden McCallum hosted events at London’s National Portrait Gallery and Eden McCallum’s Amsterdam offices. The talks were designed to show that fresh thinking and new approaches are needed to keep a business fit for the future.

Every industry and every company has some outdated practices

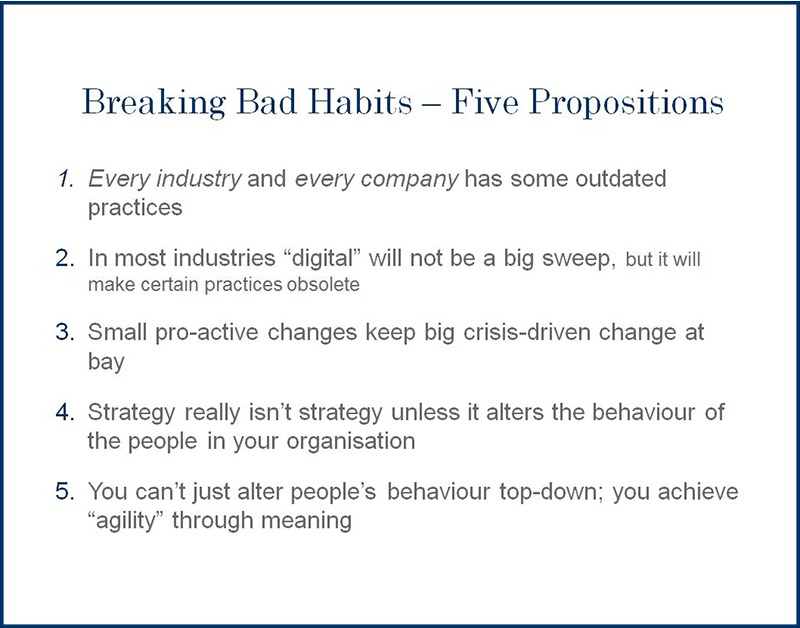

Prof Vermeulen offered five propositions in the course of his presentation. The first was that “every industry and every company has some outdated practices”.

One example is the British newspaper industry – especially the “quality” end – which until fairly recently insisted that only a broadsheet format could symbolise and guarantee seriousness, even though the product itself was unwieldy and often impractical. When Prof Vermeuelen researched why British papers were printed in this larger format, it turned out that three hundred years ago they had been taxed according to the number of pages that were used. The tax was abolished in 1835, but the big pages stayed, for no good reason. This is the sort of outdated practice that can be the source of innovation, Prof Vermeulen said. Indeed, many British newspapers had found a new lease of life when moving to a more compact format.

Another business category in which inherited (and unnecessary) practices can be found is the hotels sector. Here Prof Vermeulen cited the CitizenM hotel brand, which has, as he put it, achieved innovation through the elimination of outdated practices.

CitizenM hotels offer comfortable but simple rooms, in hotels with no concierge services, no restaurant or spa or gym. You check in using your credit card. By stripping out inessentials the price can be kept down – a comfortable room can be had for $180 a night on Fifth Avenue, New York City. This focus on the core value proposition echoes the approach taken by Eden McCallum, as Prof Vermeulen cites in his book. Independent consultants concentrate on the project in hand and are not bogged down in internal bureaucracy nor are they paid for ‘beach time’, keeping overhead to a minimum.

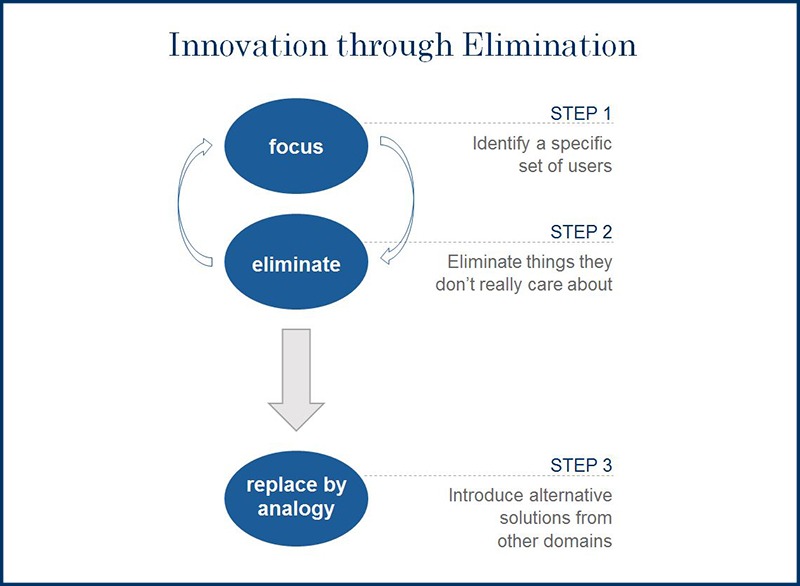

A simple three step process can deliver “innovation by elimination”, Prof Vermeulen said. First, identify a specific set of users (your product or service isn’t for everybody). Second, eliminate things these users don’t really care about. Third, introduce alternative solutions from other domains. For example, CitizenM uses yield management pricing instead of booking out rooms at large discounts far in advance, the common practice in much of the hotels business.

This third step – looking elsewhere for ideas – is particularly interesting. “You can’t learn much from your closest competitors,” Prof Vermeulen said. “They are already like you.” Other businesses may offer more inspiration.

In most industries ‘digital’ will not be a big sweep, but it will make certain practices obsolete

The second of the five propositions was: “In most industries ‘digital’ will not be a big sweep, but it will make certain practices obsolete.” CitizenM hotels exemplify this too: customers may use TripAdvisor instead of a concierge for restaurant recommendations, and check-in with a credit card rather than with a receptionist.

Small pro-active changes keep big crisis-driven change at bay

Prof Vermeulen’s third proposition was that “small pro-active changes keep big crisis-driven change at bay”. Here he was developing a theme first set out in his HBR article (“Change for change’s sake”, 2010) a few years ago. Waiting for a crisis to make big changes is costly. It is also too late. Keeping an organisation nimble, ready for and used to change, is better.

Alfred West, chief executive of the investment firm SEI, says that he never gets change completely right, but that the process of regular change in itself helps. “In a world in which the business environment can change overnight [it] gives SEI the flexibility and the mindset to transform itself just as quickly,” Mr. West says.

Strategy really isn’t strategy unless it alters the behaviour of the people in your organisation

The fourth proposition was that “strategy really isn’t strategy unless it alters the behaviour of the people in your organisation”. This is a crucial insight. “If people don’t change what they are doing then this strategy will just remain a PowerPoint deck,” Prof Vermeulen said.

He cited a study by Ryan Buell from Harvard Business School which showed that chefs in a kitchen felt motivated to prepare breakfasts more carefully if they could see the face of the customer on an iPad in the kitchen. Another experiment led by Adam Grant at Wharton showed that university fundraisers achieved much higher totals when they could understand the value of the work (a student came and explained what his bursary had meant to him). And another study led by Jana Gallus at UCLA showed that wikipedia editors raised their productivity when they were sent a Jpeg of an Edelweiss flower as an acknowledgement of their efforts.

All these examples confirm that strategy remains a dry abstraction unless the people actually doing the work can see the point of it and feel motivated to carry it out. Simple and inexpensive “nudges” help employees find meaning in their work, which leads to behavioural change.

You don’t alter people’s behaviour top-down; you achieve agility through meaning

This leads to the fifth and final proposition: “you don’t alter people’s behaviour top-down; you achieve agility through meaning”. Financial incentives don’t work over the longer term; small changes in behaviour do.

In conclusion…

Winning, paradoxically, can be bad for you, if those victories lead to bad habits setting in. Prof Vermeulen has shown that fresh thinking and new approaches are needed to make work meaningful and to maintain your competitive edge.