The Neuroscience of Hybrid Working

“The psychological and emotional impact of the Covid pandemic has been described as the equivalent to surviving a car crash”

The shock of lockdowns – of interrupted working patterns and new working-from-home arrangements – has taken a toll. Many report feelings of tiredness, “brain fog” and even exhaustion. But what has really happened to us over the past 18 months or so, and how might we learn to cope better with these new, changed circumstances?

Eden McCallum invited Cristina Escallón to give a presentation on the neuroscience of hybrid working. Escallón is a highly regarded lecturer and consultant on leadership and neuroscience. Her talk revealed a wealth of detail about the psychological and emotional “car crash” of the Covid pandemic and its consequences.

Escallón began with a process known as a “check in”, an exercise to gauge the mood and emotional state of a team or audience. This technique was developed in the aviation industry, as it turns out that accidents stem more often from problems in flight crews’ mindsets and mood than from mechanical failure. Once this was recognized, it became industry practice to ask employees to report regularly on how they are feeling.

And Escallón’s audience, a group of professionals invited by Eden McCallum, was feeling pretty tired and stressed, like so many others. But some also expressed gratitude, which has been the predominant emotion Escallón has observed through the whole pandemic, with every single group she has worked with (across all continents, industries and different socio-economic strata).

A fundamental principle of neuroscience, Escallón explained, is that humans instinctively want to move away from threats and towards rewards – but that fear of the bad is stronger than the appeal of the good. A tired brain worries and reacts more than a rested one. After 18 months of pandemic, our brains are exhausted and less capable- emotionally, socially and cognitively. We need to retrain and rest.

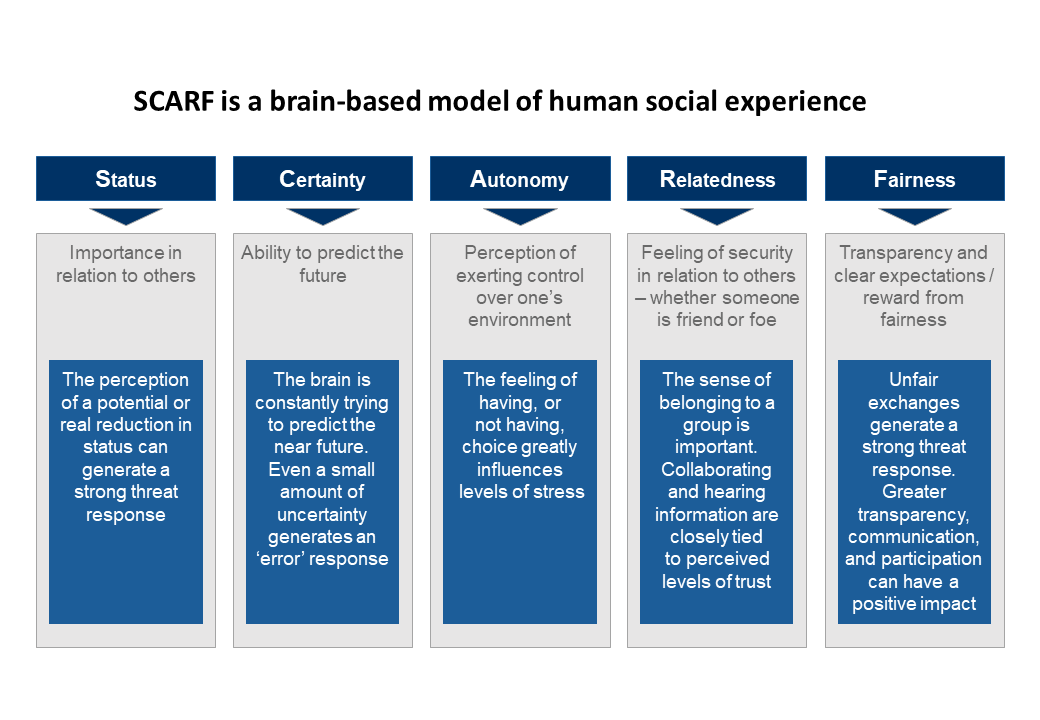

In the field of neuroscience a well-established model, developed by David Rock of the Neuroleadership Institute, describes five key factors which activate threat or reward responses in the brain. It is known as the SCARF model, and the acronym is made up of five headings: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.

It is worth considering briefly how each of these aspects have been affected during this time. Certainty, Autonomy and Relatedness were hit hard throughout the pandemic; Status and Fairness are being threatened more for many now, as part of these new, emerging ways of working.

The loss of office-based life and familiar work routines has involved a certain loss of perceived Status for some, in particular as all boxes are the same on video calls. We have clearly all suffered from a lack of Certainty over the past 18 months. The impact on Autonomy is a mixed picture. While we largely lost it at the beginning, many of us then realized we had gained greater flexibility in how we manage our lives. The brain does not want to let go of that reward. Relatedness was bound to suffer as connections between loved ones and colleagues were interrupted, threatening the brain through disconnection (most mammals survive by operating in ‘packs’). And Fairness is being challenged now, as a return to the office raises all sorts of differences (e.g. who can work from home vs not).

In other words, Escallón said, all five elements in the SCARF model have been rocked during the pandemic. “Our brains have been under siege”. Even if you are feeling ok on the surface other things may be happening at an unconscious level. This may help explain the feelings of tiredness, stress and “brain fog” reported by many.

But we had better get used to hybrid working. Multiple research studies show that 50-70% of people prefer a hybrid model going forward. People can save as much as 90 minutes a day in avoided commuting time, using half that time to complete work tasks and half for personal matters. So productivity can rise even as people enjoy greater flexibility.

What has been called the “Great Resignation” in the US (and also making way in parts of Europe) reflects the big shift in ways of working, but also in the expectations of workers. Escallón suggested three reasons why this is happening. First, people have had an opportunity to consider what their true priorities in life are. Second, some have regained more autonomy over their lives and are not willing to give it up. And third, many opportunities have opened up in the labour market.

The pros and cons of office life have also become more apparent. There is more relatedness in the office and communication is enhanced by observing body language and other non-verbal cues. People feel it is much better for group problem-solving as well as on-boarding new team members. But clearly commuting takes time and energy, and currently exposes the commuter to greater health risk. Some people simply prefer working from home. Managing the hybrid world requires a strategic understanding of employee preferences, and of what work needs to be done where. Listening to employees will be vital. One thing is certain, views tend to be held passionately.

Backed by work from the Neuroleadership Institute, Escallón suggests the task for leaders is to “solve for autonomy but manage for fairness”. This means giving teams guidelines, but letting them decide on the specifics of how to balance delivering what the business needs with individual team needs. It is important to be intentional about this and communicate why certain decisions have been made.

“We can make simple changes to meetings to make them more ‘brain friendly’”

Escallón suggested we should consider introducing “brain-friendly practices,” in particular into our meetings. First of all, be clear how you frame the discussion at the outset. “We need to do the prep for brains that are exhausted,” she said. This means being intentional and clear, and probably reducing the number of meetings we have.

Neither a hybrid meeting format (some online, some in the room), nor the all online meeting format, is ideal. Both have drawbacks. But it is clear that those not in the room can feel left out and the power dynamics are uneven. The cognitive load of knowing when to look into a camera, or not, can be heavy and unnatural for those ‘in person’.

For this reason Escallón supports the idea of ‘one virtual all virtual’. It may not feel great, but there is some evidence to suggest that the quality of interaction in an all-online meeting is better, if well facilitated. That is what she has experienced over the past 18 months, having facilitated over 300 days of workshops virtually herself.

Scheduling can also make a difference. Brains work better when they are rested, so most people tend to do better, deeper or creative thinking on Mondays and on weekday mornings when we are fresher (though ‘night owls’ in the webinar did comment that they do best at night). We should consider how we schedule the week; and also cut meetings shorter so we are not back-to-back. “The brain and body need regular breaks”, she said.

“Conflict is in the air and leaders need to be skilled at managing it”

Our social skills have deteriorated because social interaction reduced dramatically for most people over the past 18 months. There are also new and emotive sources of conflict, driven by different points of view on things like perceived health risks, the broader social impact of restrictions, the need for social distancing and masking, who should be vaccinated, where people work, etc. An emotionally drained workforce means there is more potential for conflict in the air (Escallón published an article on LinkedIn on May 16, 2021 on this topic). When we are tired and stressed, we are more likely to be triggered even by minor events or comments.

Escallón says we have to get better at recognising that there are lots of potential sources of stress in teams, manage our own triggers and learn how to de-escalate conflict.

What can we do to manage potential trigger situations? First, notice what is going on and pause, for example by counting to 10 or going for a walk. The objective is to slow down the heart rate and give the pre-frontal cortex, the rationale part of your brain, a chance to come online again. Second, label the emotions, which helps you recognise what is going on and switch the energy from your emotional brain to your thinking brain. Third, reframe the situation through questions of the mind or heart- e.g. ‘What can I learn from this?’ (growth, mind) or ‘What might they be going through that made them react that way’ (empathy, heart), without judging or assuming negative intention.

“Trust is the key to all relationships, and trust has been rocked.”

Building trust is essential at a time like this, and trust is contextual. Through years of her own research, Escallón believes that our willingness to take a risk is based on an implicit assessment we make of somebody, based on 3 factors she codifies as AIR – Ability (what colleagues can do), Intention (why do they do it) and Reliability (how do they do it).

The interesting insight is that we all have different trust profiles, for example some value reliability very highly, while others put much more weight on intention. An interesting exercise for any team is for each person to write down the 5 words they most associate with trust and then compare how many are identical across the group; usually, zero, says Escallón, having done this work hundreds of times for more than a decade. To build trust, we need to make our trust models explicit to ourselves and each other, she said.

Interestingly, in a hybrid working world, in which is it harder to ‘see’ what people are doing, reliability becomes more important.

We were thrown into this pandemic without warning; bringing awareness to what we, our brains and hearts have been through, and being thoughtful about how we manage this next phase, can only help us and our organisations be better prepared for what comes next.