The surprising power of people and computers thinking together: Professor Thomas Malone on ‘Superminds’

Summary of discussion hosted by Eden McCallum at the Royal Society

“We often over-estimate the potential of AI. It is easy to imagine computers as smart as people, but unfortunately it is much harder to create them. On the other hand, we often under-estimate the potential of hyperconnectivity, perhaps because it is easier to create hyperconnectivity than to imagine it.”

We are offered, on a regular basis, scary-sounding predictions about how many jobs computers are going to “destroy”, and how vulnerable mere human beings are to the coming dominance of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Some people like horror stories, and the march of the machines is sometimes presented as one.

Thomas Malone has a far more encouraging take, and he shared it with an audience of business leaders hosted by Eden McCallum at the Royal Society before Christmas.

Prof Malone is the founding director of MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence and the Patrick J. McGovern Professor of Management at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. His 2004 book The Future of Work accurately anticipated how new technology would influence and affect modern working patterns.

He has set out his current thinking in a new book: Superminds – the surprising power of people and computers thinking together, and his presentation gave us a flavour of what can be found in its pages.

Prof Malone opened with two specific suggestions. First, that we should spend less time thinking about ‘people or computers’, and more time thinking about ‘people and computers’. We should worry a bit less about which jobs computers are going to take away from people, and spend more time thinking about what people and computers can do together that could never have been done before.

His second big thought was that we need to see the world in a new way. We have to spot what he called “ghosts” – “Not real ghosts,” Prof Malone said, “but powerful entities that are all around us all the time, that are mostly invisible unless you know how to look. These ghosts are superminds, groups of individuals acting collectively in ways that seem intelligent.”

These superminds come in all shapes and sizes, Prof Malone said. Every hierarchical company we know is a supermind. Every democracy is a supermind (although they may not always seem to be acting very intelligently). Every market is a supermind. Every scientific community is a supermind. Every local neighbourhood (where people interact) is a supermind.

What is more, almost everything that human beings have achieved, every important invention, has been achieved by superminds, not by individuals working alone, but by groups of people working together over time and space.

This fundamental insight lies at the heart of Prof Malone’s new book, and also explains his cautious optimism about the future. If we can draw upon the complementary strengths of man and machine, and get them to work together, a better future could be built. In fact, we may have no choice. “If you want to accomplish almost anything in the world you have to somehow influence or work with these superminds,” he said.

What are the striking examples of superminds – this powerful combination of human beings and technology – which we may not until now have recognised as such? Wikipedia is one – the largest encyclopaedia the world has ever known, built on the back of human intelligence and the capacity of the internet to spread and share knowledge.

Another example is the Polymath project, which has involved dozens of mathematicians from all over the world, most of whom had never met before, who worked together online to prove a theorem in a way that had never been done before.

A negative example of a harmful supermind is the phenomenon of “fake news”. In this case computers have made superminds more stupid, Prof Malone said.

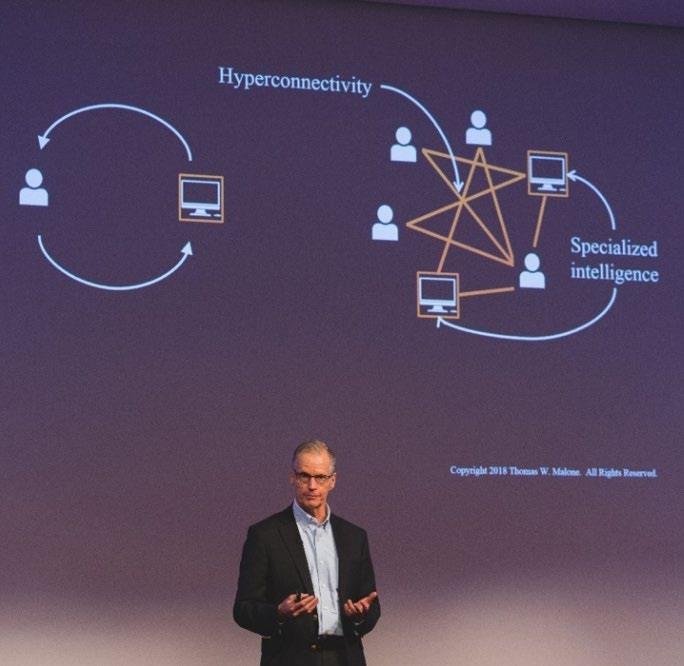

The practical question is: how can people and computers be connected so that collectively they act more intelligently than before? To answer this Prof Malone explained that we need to recognise we are really talking about two different types of intelligence: specialised and general.

Computers, even the most advanced ones, have only specialised intelligence, he said. The IBM Watson programme was only good at one thing – playing the game Jeopardy (i.e., answering questions). It could not play chess. This is true for all AI programmes, Prof Malone explained: “A five-year-old child has more general intelligence than the most powerful computers.”

While many predict a time, coming soon, when AI will be “smarter” than human beings, Prof Malone reminded us that people have been saying this for decades. The cross-over point is always estimated to be about 20 years away – it has been since the 1950s. Prof Malone said such a moment may come but it will in fact be “many, many decades in the future.”

Until then we will need humans. “All uses of computers will have to involve people,” he explained. This is sometimes known as having “humans in the loop”. But a better way of thinking, Malone said, is to have “computers in the group.” Then computers can use their specialized intelligence for tasks like mathematics, and humans can use their general intelligence for everything else. More importantly, computers can provide hyperconnectivity, connecting people to other people at much larger scales and in rich new ways that were never possible before. And this is what is powerful.

Until then we will need humans. “All uses of computers will have to involve people,” he explained. This is sometimes known as having “humans in the loop”. But a better way of thinking, Malone said, is to have “computers in the group.” Then computers can use their specialized intelligence for tasks like mathematics, and humans can use their general intelligence for everything else. More importantly, computers can provide hyperconnectivity, connecting people to other people at much larger scales and in rich new ways that were never possible before. And this is what is powerful.

“We often over-estimate the potential of AI,” Prof Malone said. “It is easy to imagine computers as smart as people, but unfortunately it is much harder to create them. On the other hand, we often under-estimate the potential of hyperconnectivity, perhaps because it is easier to create hyperconnectivity than to imagine it.”

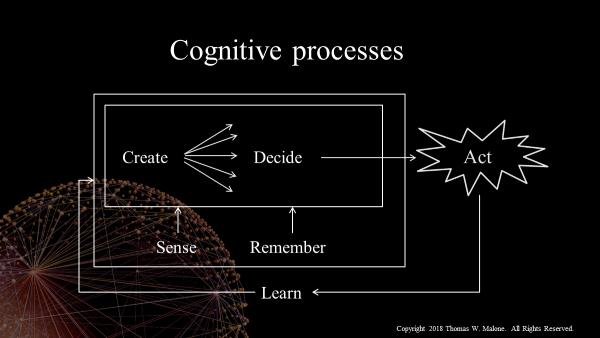

For businesses the potential is to augment and improve the cognitive processes of creating options and making decisions by drawing on this hyperconnectivty and using the power of superminds. This is a three-step process. First, sense the world around us. Second, remember the past. And third, learn from experience over time. Computers can help us to do all these things more intelligently and powerfully.

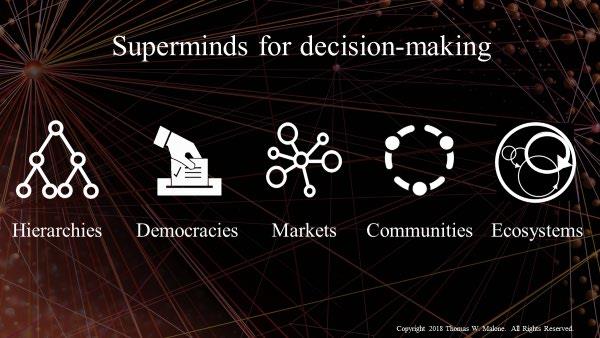

In terms of decision making, Prof Malone has identified five different types of superminds:

- Hierarchies – where group decisions are delegated to specific individuals.

- Democracies – where group decisions are made by voting

- Markets – where the group decision is the sum of all the individual agreements between buyers and sellers.

- Communities – where group decisions are made by a kind of informal consensus based on shared norms and reputations

These all require co-operation. But there is a fifth kind of supermind:

- Ecosystems – where group decisions are made by the law of the jungle (whoever has the most power gets what they want), or by the survival of the fittest. This mode is always there lurking in the background.

Interesting experiments have been carried out using superminds, for example, the “Good Judgment Project”, led by the University of Pennsylvania, and funded by the US intelligence community. Here volunteers, not experts, were invited to forecast the future outcomes of a number of geopolitical events. The 2% most accurate out of the volunteers were then selected and these ‘super forecasters’ worked in teams of 12-15 people. Their predictions were combined using statistical techniques. These “super forecasters” were not experts on geo-politics, but just people who were good at thinking logically about events. The results? They were 30% better at forecasting than professionals from the US intelligence services, who had access to top secret intercepts and other classified material.

In the field of medicine, the “Human Diagnosis Project” has also been impressive. Here medical opinions on difficult cases from physicians around the world have helped deliver more accurate diagnoses and better clinical care. It has formed into a community as well as a hierarchy, taking advantage of hyperconnectivity. It has built up a knowledge base of medical examples. When you then apply machine learning algorithms you have a powerful diagnosing supermind.

A similar phenomenon has been found when humans and computers combine to analyse American football and predict the what will happen in the next play. The combination of people and computers is more accurate than either people alone or computers alone.

And lastly, back in a business setting, Prof Malone argued that corporate strategic planning could be improved by using many more people in the process than would usually be done, with people from all levels in the business helping create new options/ideas and predict outcomes to aid decision-making, all supported by technology such as online contests and prediction markets. He also gave examples of how technology can improve humans’ ability to sense, remember and learn in a business context. Amazon experiments in this way, trying different approaches to pricing and learning what works best.

In the Q&A session after his talk one member of the audience asked whether rebel or non-conformist voices might be shut out of such a decision-making process. On the contrary, Prof Malone said, the most collectively intelligent superminds often have more diversity of thought.

In the Q&A session after his talk one member of the audience asked whether rebel or non-conformist voices might be shut out of such a decision-making process. On the contrary, Prof Malone said, the most collectively intelligent superminds often have more diversity of thought.

It was an information-packed hour. But also a positive and encouraging one. Superminds are rich in potential. Computers dispassionately optimise statistics and data, Prof Malone said. Humans bring general intelligence and experience. It is a powerful combination when made to work together properly.

He ended with an even more ambitious thought. “It is becoming increasingly useful to view all the people and computers on our planet as part of a single global supermind,” he said. “And perhaps our future as a species may depend on whether we are able to use our global supermind to make decisions that are not just smart but also wise.”